Canada in the American Civil War

I make no attempt to capture all of the American Civil War's connection to Canada. However, I have capsulized some interesting events that impacted these tumultuous times. Hopefully the following summaries will provide some insight into the Civil War and its influence on Canada. You may also see why the fascination in this world changing event still exists today.

For well-researched and interesting books on the subject, I recommend Canadians In The Civil War by Claire Hoy and Blood and Daring - How Canada Fought the American Civil War and Forged a Nation by John Boyko.

For well-researched and interesting books on the subject, I recommend Canadians In The Civil War by Claire Hoy and Blood and Daring - How Canada Fought the American Civil War and Forged a Nation by John Boyko.

The United States Civil War was America's bloodiest conflict. From 1861 to 1865, over 3 million soldiers fought, and an estimated 750,000 died. This battle, which divided the country and saw brother against brother, community against community and family against family, haunts the United States to this day.

The world watched closely as the events unfolded. Up to this point, the United States had been perceived as a model of human rights and their economic and industrial growth was the envy of the world. Outside of the United States, perhaps no other country was impacted by this war more than Canada (British North America at the time). Canadians have an enduring fascination with the conflict and were very much participants in this extraordinary time in history. The war, in fact, threatened the very existence of Canada and created the necessity for the weak Canadian colonies to band together to withstand the annexation dreams of many in Washington. In many ways, it was a three-way battle of visions for the future of the North American continent. There was the northern vision, led by Abraham Lincoln, the southern vision of Jefferson Davis and the Canadian vision led by John A. Macdonald.

The United States was Canada’s traditional enemy from the beginning. There was much blood spilled between the two peoples during the Seven Years War (1756-1763), the 1775 American invasion and the War of 1812. The years of peace prior to the Civil War was an uneasy one, given the Americans' sense of Manifest Destiny, which dictated that they were destined to envelop all of North America into the United States. John Boyko, an historian and administrator at Lakefield College School and author of several books, reminds us that the Americans and Canadians were bad neighbors. Canadians viewed Americans with a careful eye, and the mistrust only increased when the war between the states erupted in 1861. During these years of "wholesale slaughter," the Canadians watched, participated and learned. The structure and nature of what the Canadian government is was very much determined by the failure of the United State Government to keep their country unified without first almost tearing the people apart.

The world watched closely as the events unfolded. Up to this point, the United States had been perceived as a model of human rights and their economic and industrial growth was the envy of the world. Outside of the United States, perhaps no other country was impacted by this war more than Canada (British North America at the time). Canadians have an enduring fascination with the conflict and were very much participants in this extraordinary time in history. The war, in fact, threatened the very existence of Canada and created the necessity for the weak Canadian colonies to band together to withstand the annexation dreams of many in Washington. In many ways, it was a three-way battle of visions for the future of the North American continent. There was the northern vision, led by Abraham Lincoln, the southern vision of Jefferson Davis and the Canadian vision led by John A. Macdonald.

The United States was Canada’s traditional enemy from the beginning. There was much blood spilled between the two peoples during the Seven Years War (1756-1763), the 1775 American invasion and the War of 1812. The years of peace prior to the Civil War was an uneasy one, given the Americans' sense of Manifest Destiny, which dictated that they were destined to envelop all of North America into the United States. John Boyko, an historian and administrator at Lakefield College School and author of several books, reminds us that the Americans and Canadians were bad neighbors. Canadians viewed Americans with a careful eye, and the mistrust only increased when the war between the states erupted in 1861. During these years of "wholesale slaughter," the Canadians watched, participated and learned. The structure and nature of what the Canadian government is was very much determined by the failure of the United State Government to keep their country unified without first almost tearing the people apart.

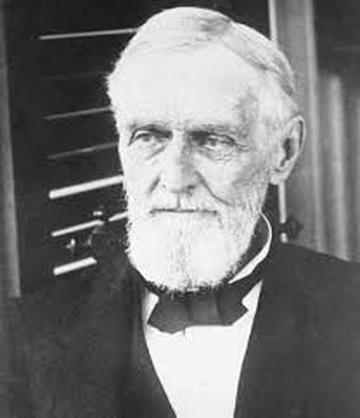

WILLIAM SEWARD

WILLIAM SEWARD

Since 1850, William Seward, the American Secretary of State during the Civil War, had promoted the annexation of British North America and felt that it was destined to become part of the United States. As it became obvious towards the end of the Civil War that the North would emerge victorious, there was a fear that American expansionism would rear its head and turn its eyes to the north. British and Canadian officials responded accordingly by enhancing fortifications, stationing thousands of soldiers along the border and deploying the Royal Navy.

But despite the historical animosity between the two countries, up to 55,000 men from Canada served in the Union army, and hundreds joined the Confederate army. The reasons many Canadians supported the South varied. Some young men had a the sense of romance and fought the war against “northern aggression.” Some felt a sympathy for the Southern Culture and slavery.

The number of Canadians that participated in this war is quite impressive given that the total population was less than 3 million at the time. Many had already immigrated to the United States, while some young men were volunteers who signed up from their Canadian home to escape an oppressive life or to collect the offered bounties of $200 or more. Many more were pressed into service involuntarily by unscrupulous "crimps," who, in cahoots with U.S. military authorities, prowled our borders looking for young men to either cajole, drug or kidnap into service. Canadians fought in every major battle, 29 earned the Congressional Medal of honor and Canadians were present at Lee's surrender.

But despite the historical animosity between the two countries, up to 55,000 men from Canada served in the Union army, and hundreds joined the Confederate army. The reasons many Canadians supported the South varied. Some young men had a the sense of romance and fought the war against “northern aggression.” Some felt a sympathy for the Southern Culture and slavery.

The number of Canadians that participated in this war is quite impressive given that the total population was less than 3 million at the time. Many had already immigrated to the United States, while some young men were volunteers who signed up from their Canadian home to escape an oppressive life or to collect the offered bounties of $200 or more. Many more were pressed into service involuntarily by unscrupulous "crimps," who, in cahoots with U.S. military authorities, prowled our borders looking for young men to either cajole, drug or kidnap into service. Canadians fought in every major battle, 29 earned the Congressional Medal of honor and Canadians were present at Lee's surrender.

Relations between Canada and the North were not helped by the open gloating of many Canadians and some of their newspapers over the fast-collapsing republican experiment to the south.

Claire Hoy, in his book Canadians in the Civil War, observes that during the American Civil War many Canadian cities, especially Toronto and Montreal, welcomed a well-financed network of Confederate spies and adventurers who launched cross-border raids. Montreal's St. Lawrence Hall Hotel had so many Confederates living there it offered mint juleps on its menu. John Wilkes Booth made several trips to Montreal and to Toronto as part of an organized plot leading up to the 1865 assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. Southern sympathies were so prominent in Halifax, where blockade-running created several family fortunes, that some businesses openly flew Confederate flags and traded in Confederate currency. There were calls throughout the North for American troops to cross the border in retaliatory expeditions.

Claire Hoy, in his book Canadians in the Civil War, observes that during the American Civil War many Canadian cities, especially Toronto and Montreal, welcomed a well-financed network of Confederate spies and adventurers who launched cross-border raids. Montreal's St. Lawrence Hall Hotel had so many Confederates living there it offered mint juleps on its menu. John Wilkes Booth made several trips to Montreal and to Toronto as part of an organized plot leading up to the 1865 assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. Southern sympathies were so prominent in Halifax, where blockade-running created several family fortunes, that some businesses openly flew Confederate flags and traded in Confederate currency. There were calls throughout the North for American troops to cross the border in retaliatory expeditions.

SECORD MONUMENT

SECORD MONUMENT

Four Union generals were Canadian-born, along with 29 Medal of Honor winners. And while most combatants fought for the North, the only monument in Canada to a Civil War veteran sits in Kincardine, Ontario, a tribute to Dr. Solomon Secord, a surgeon with the 20th Georgia Volunteers and the grandnephew of the War of 1812 heroine Laura Secord. Indeed, Canadian involvement in the Civil War is rather impressive. Up to 1865, enlistment in the Civil War was the greatest concentration of Canadians for a war effort. This number was unmatched until the enlistment in World War I and World War II. In contrast to the American states, Canadian enlistment provided the 13th largest number of troops for the Union cause, surpassing that of several states. The total of Canadians wearing blue exceeded the size of Robert E. Lee's army (approximately 45,000) when it surrendered at Appomatox Court House on April 12, 1865. Given the numbers and Lee's capacity to win in the face of larger armies, one must wonder what kind of difference it might have made had those boys worn grey instead of blue.

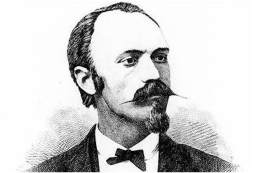

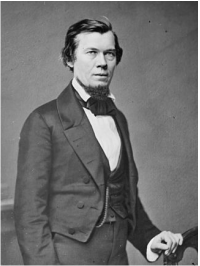

CLEMENT VALLANDIGHAM

CLEMENT VALLANDIGHAM

The Copperhead faction of anti-war democrats hated Lincoln. They wanted the war stopped and the Confederacy preserved and, failing that, they demanded the formation of a new country comprised of several Midwest states. The Copperhead's chief spokesman was Clement Vallandigham, who inspired the Copperheads and campaigned to be governor of Ohio from his headquarters in Windsor, Ontario.

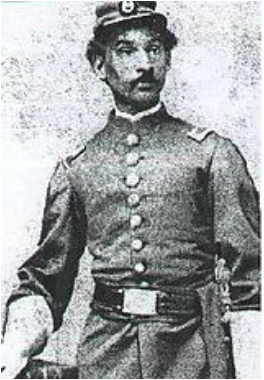

ANDERSON RUFFIN ABBOTT

ANDERSON RUFFIN ABBOTT

Anderson Ruffin Abbott was the first Black Canadian to be licensed as a physician. Toronto-born, he was the son of a family who had left Alabama as free people of color after their store had been ransacked. After living a short time in New York, the Abbotts relocated to Upper Canada in 1835.

Abbott applied for a commission as an assistant surgeon in the Union Army in February 1863, but his offer was evidently not accepted. That April, he applied to be a medical cadet in the United States Colored Troops, but was finally accepted as a civilian surgeon under contract. He served in Washington, D.C. from June 1863 to August 1865, where he received numerous commendations and became popular in Washington society.

Abbott was one of only thirteen black surgeons to serve in the Civil War, a fact that fostered a friendly relationship between him and the president. On the night of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, Abbott accompanied Elizabeth Keckley to the Peterson House and returned to his lodgings that evening. After Lincoln's death, Mary Todd Lincoln presented Abbott with the plaid shawl that Lincoln had worn to his 1861 inauguration.

Abbott applied for a commission as an assistant surgeon in the Union Army in February 1863, but his offer was evidently not accepted. That April, he applied to be a medical cadet in the United States Colored Troops, but was finally accepted as a civilian surgeon under contract. He served in Washington, D.C. from June 1863 to August 1865, where he received numerous commendations and became popular in Washington society.

Abbott was one of only thirteen black surgeons to serve in the Civil War, a fact that fostered a friendly relationship between him and the president. On the night of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, Abbott accompanied Elizabeth Keckley to the Peterson House and returned to his lodgings that evening. After Lincoln's death, Mary Todd Lincoln presented Abbott with the plaid shawl that Lincoln had worn to his 1861 inauguration.

Benjamin Wier

Benjamin Wier

Born in 1805, Benjamin Wier was a prominent and controversial Halifax entrepreneur and politician who collaborated with the confederate blockade runners. Profit rather than patriotism probably motivated this activity. Wier gave Confederates access to ship repair facilities in Halifax. In return, Confederates provided him with cotton supplies which he sold to Britain. It was a lucrative arrangement for Wier. After the South lost the war, Wier managed to re-establish trade with northern businesses but he couldn't appease the U.S. government,

which refused to grant him a visa to step on American soil.

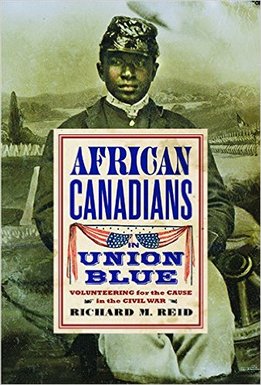

Before Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, he made a last-minute change - a paragraph authorizing the army to recruit black soldiers. Over the next two years, approximately 180,000 soldiers and 18,000 sailors joined the cause. Several thousand came from Canada, the terminus of the Underground Railroad.

What compelled these young men to leave the comfort and safety of home to face death on the battlefield, loss of income for their families, and legal sanctions for participating in a foreign war? Drawing on newspapers, autobiographies, and military and census records, Richard Reid pieces together a portrait of a group of men who served the Union in disparate ways - as soldiers, sailors, or doctors - but who all believed that the principles of liberty, justice, and equality were worth fighting for, regardless of which side of the border they made their home.

By bringing the courage and contributions of these men to light, African Canadians in Union Blue opens a window on the changing nature of the Civil War and the ties that held black communities together even as the borders around them shifted or were torn asunder.

CALIXA LAVALLEE

CALIXA LAVALLEE

Calixa Lavallée was a French-Canadian musician and Union officer during the War. He later composed the music for “ O Canada,” which officially became the national anthem of Canada in 1980. In 1857, he had moved to the United States and lived in Rhode Island where he enlisted in the 4th Rhode Island Volunteers of the Union army during the War, attaining the rank of lieutenant.

SARAH EMMA EDMONDS

SARAH EMMA EDMONDS

The man known as Franklin Flint Thompson to his fellow soldiers was really a woman, Sarah Emma Edmonds, one of the few females known to have served during the Civil War. Edmonds was born in Canada in 1841. Desperate to escape an abusive father and forced marriage, she moved to Flint, Michigan in 1856, where she discovered that life was easier when she dressed as a man. she enlisted in the 2nd Michigan Infantry as a male field nurse.

As "Franklin Flint Thompson," Edmonds participated in several battles, including Second Battles of Manassas and Antietam. As a field nurse, she would be dealing with mass casualties, especially at Antietam, which is known as one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War.

She also served as a Union spy and infiltrated the Confederate army several times, although there is no official record of it. One of her alleged aliases was as a Southern sympathizer named Charles Mayberry. Another was as a black man named Cuff, for which she disguised herself using wigs and silver nitrate to dye her skin. And yet another was as Bridget O'Shea, an Irish peddler selling soap and apples.

Malaria eventually forced Edmonds to give up her military career, since she knew she would be discovered if she went to a military hospital. Her being listed as a deserter upon leaving made it impossible for her to return after she recovered. Nevertheless, she still continued serving her new country, again as a nurse, though now as a female one at a hospital for soldiers in Washington, D.C.

In 1865, Edmonds published her experiences in the bestselling Nurse and Spy in the Union Army, and went on to marry and have children. But her heroic contributions to the Civil War were not forgotten: she was awarded an honorable discharge from the military, a government pension, and admittance to the Grand Army of the Republic as its only female member.

As "Franklin Flint Thompson," Edmonds participated in several battles, including Second Battles of Manassas and Antietam. As a field nurse, she would be dealing with mass casualties, especially at Antietam, which is known as one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War.

She also served as a Union spy and infiltrated the Confederate army several times, although there is no official record of it. One of her alleged aliases was as a Southern sympathizer named Charles Mayberry. Another was as a black man named Cuff, for which she disguised herself using wigs and silver nitrate to dye her skin. And yet another was as Bridget O'Shea, an Irish peddler selling soap and apples.

Malaria eventually forced Edmonds to give up her military career, since she knew she would be discovered if she went to a military hospital. Her being listed as a deserter upon leaving made it impossible for her to return after she recovered. Nevertheless, she still continued serving her new country, again as a nurse, though now as a female one at a hospital for soldiers in Washington, D.C.

In 1865, Edmonds published her experiences in the bestselling Nurse and Spy in the Union Army, and went on to marry and have children. But her heroic contributions to the Civil War were not forgotten: she was awarded an honorable discharge from the military, a government pension, and admittance to the Grand Army of the Republic as its only female member.

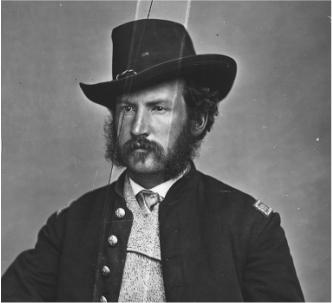

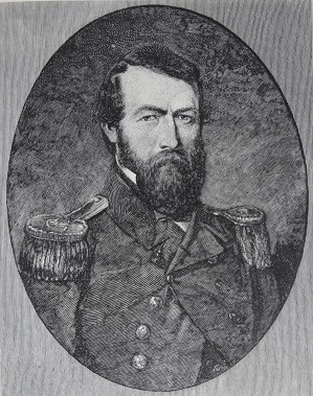

EDWARD P. DOHERTY

EDWARD P. DOHERTY

Canadian-born Edward P. Doherty was a Union army officer who formed and led the detachment of Union soldiers that captured and killed John Wilkes Booth in a Virginia barn on April 26, 1865, 12 days after Lincoln was fatally shot. His command consisted of 26 enlisted men of the 16th New York Cavalry and 2 detectives making a total of 29 men. Doherty's own account reveals the leading role he played in the events that led to him being called the 'avenger of Lincoln's assassin:

"Booth all this time was very defiant and refused to surrender. Booth up to this time had denied there was anyone in the barn besides himself. Considerable conversation now took place between myself, Booth and the detectives. We threatened to burn the barn if he did not surrender. Finally, Booth said, 'oh Captain, there is a man here who wants to surrender awful bad'. I ordered Garrett, the younger son, who had the key to unlock the barn, which he did. I partially opened the door and told Herold to put out his hand, which he did. I told him to put out his other hand. I took hold of both his wrists and pulled him out of the barn. Almost simultaneous with my taking Herold out, the hay in the rear was ignited. Sergt. Corbett shot the assassin Booth, wounding him in the neck. I entered the barn as soon as the shot was fired, dragging Herold with me and found that Booth had fallen on his back. The assassin Booth lived for about two hours, said Doherty in his official report. I would say that great credit is due to all concerned for the fortitude and eagerness they displayed in pursuing and arresting the murderers. For nearly 60 hours hardly an eye was closed or a horse dismounted until the errand was accomplished. In conclusion I beg to state that it was afforded my command and myself inexpressible pleasure to be the humble instruments of capturing the foul assassins who caused the death of our beloved President and plunged the nation in mourning."

"Booth all this time was very defiant and refused to surrender. Booth up to this time had denied there was anyone in the barn besides himself. Considerable conversation now took place between myself, Booth and the detectives. We threatened to burn the barn if he did not surrender. Finally, Booth said, 'oh Captain, there is a man here who wants to surrender awful bad'. I ordered Garrett, the younger son, who had the key to unlock the barn, which he did. I partially opened the door and told Herold to put out his hand, which he did. I told him to put out his other hand. I took hold of both his wrists and pulled him out of the barn. Almost simultaneous with my taking Herold out, the hay in the rear was ignited. Sergt. Corbett shot the assassin Booth, wounding him in the neck. I entered the barn as soon as the shot was fired, dragging Herold with me and found that Booth had fallen on his back. The assassin Booth lived for about two hours, said Doherty in his official report. I would say that great credit is due to all concerned for the fortitude and eagerness they displayed in pursuing and arresting the murderers. For nearly 60 hours hardly an eye was closed or a horse dismounted until the errand was accomplished. In conclusion I beg to state that it was afforded my command and myself inexpressible pleasure to be the humble instruments of capturing the foul assassins who caused the death of our beloved President and plunged the nation in mourning."

ELIZABETH LEE'S TOMBSTONE

ELIZABETH LEE'S TOMBSTONE

Across the Detroit River and Lake St. Clair was freedom’s shore for slaves in the antebellum 1800s. And the Puce Memorial Cemetery just east of Windsor, Ontario became the final haven for hundreds of them and their descendants.

Now, caught between subdivision sprawl and the erosive force of a rain-swollen river, the burial ground yielded a marble tombstone in 2012 that might help one family bridge the gap between their Canadian life and their lore of kinship with one of the most storied warriors of the slavery-defending Confederacy.

The long-buried stone, decorated with a mournful willow, commemorates Elizabeth Lee, who died in 1894, and notes her marriage to Ludwell Lee, who — according to his Canadian family’s oral history — was a nephew of Gen. Robert E. Lee, who led the rebel army in the Civil War.

As told in handed-down history, Ludwell’s enslaved mother, Kizzie, was Robert E. Lee’s half-sister: Both were fathered by Revolutionary War hero Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee. (Information from article by Kristie Pearce in the National post October 16, 2011).

Now, caught between subdivision sprawl and the erosive force of a rain-swollen river, the burial ground yielded a marble tombstone in 2012 that might help one family bridge the gap between their Canadian life and their lore of kinship with one of the most storied warriors of the slavery-defending Confederacy.

The long-buried stone, decorated with a mournful willow, commemorates Elizabeth Lee, who died in 1894, and notes her marriage to Ludwell Lee, who — according to his Canadian family’s oral history — was a nephew of Gen. Robert E. Lee, who led the rebel army in the Civil War.

As told in handed-down history, Ludwell’s enslaved mother, Kizzie, was Robert E. Lee’s half-sister: Both were fathered by Revolutionary War hero Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee. (Information from article by Kristie Pearce in the National post October 16, 2011).

JOHN TAYLOR WOOD

JOHN TAYLOR WOOD

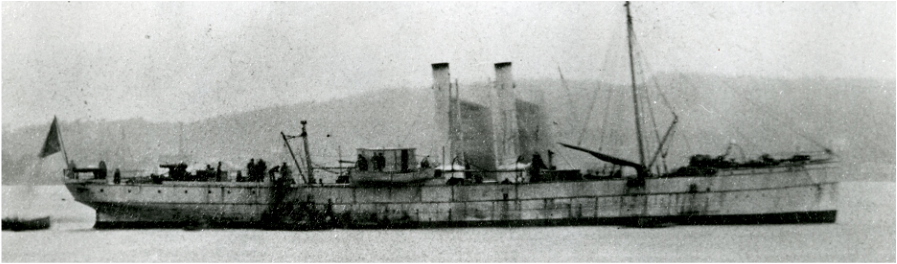

In mid-August of 1864, Halifax newspapers reported that “a strange armed vessel of rakish appearance” and manned by a crew of “thieves, felons and freebooters” had dropped anchor in the harbor. Tallahassee, a steamer outfitted as a Confederate warship, needed to refuel after mounting a series of attacks that had brought the Civil War into Northern waters. In just 10 days it had sunk or seized more than 30 unarmed merchant vessels and fishing boats off the New England coast.

Offering refuge to a Rebel commerce raider could furnish further proof of British duplicity – and provide more ammunition to Northern annexationists.

The incident was also a reminder, just two weeks before the Fathers of Confederation gathered in Charlottetown to begin building a new nation, of the urgent need for some form of colonial union to deter possible American aggression. Its commander, John Taylor Wood, was a Confederate naval officer with a reputation for boldness and a genius for commando-style raids. He was also well connected: a grandson of former U.S. president Zachary Taylor, he was the nephew of Confederate president Jefferson Davis.

By the time Tallahassee ducked into Halifax Harbour on August 18 to take on coal, a dozen Union gunboats were in pursuit. Wood had reason to expect a warm welcome. Halifax was notorious as a base for Confederate spies and ships running the blockade on Southern ports. Members of the city’s elite openly supported the Rebel cause.

There was resentment over the North’s belligerence toward Britain and its colonies and sympathy for the underdog South. “They hate the Yank as bad as we do,” observed a Confederate agent, who dubbed Halifax “a hot Southern town.”

The British and Nova Scotia governments were determined to prevent Tallahassee’s visit from escalating into another crisis. Lord Lyons, the British envoy in Washington, cabled Halifax with a warning – couched in diplomatic understatement – that the Lincoln administration was “a good deal disturbed” to learn Tallahassee was in port.

The Royal Navy admiral in charge of the Halifax station and the colony’s lieutenant governor ordered Wood to leave within 24 hours, the tightest deadline the British could impose on a belligerent vessel visiting their ports. A 12-hour extension was later granted but the message was clear – Confederate raiders would not be “coddled” in Halifax.

Wood and his crew had exposed the Union’s vulnerability at sea and spread panic among Northern ship owners, but the real damage was to the Confederate cause. The embarrassed Union Navy was forced to tighten its blockade of Wilmington, North Carolina cutting off one of the South’s last overseas supply routes. And, as Tallahassee’s crew had discovered, Southern raiders could not expect to find refuge in British colonial ports, regardless of how welcoming the populace might be.

(This Information extracted from article by Dean Jobb who is the author of Empire of Deception, the true story of a master swindler in 1920s Chicago who escaped to a new life in Nova Scotia, published in 2015 by HarperCollins Canada)..

Offering refuge to a Rebel commerce raider could furnish further proof of British duplicity – and provide more ammunition to Northern annexationists.

The incident was also a reminder, just two weeks before the Fathers of Confederation gathered in Charlottetown to begin building a new nation, of the urgent need for some form of colonial union to deter possible American aggression. Its commander, John Taylor Wood, was a Confederate naval officer with a reputation for boldness and a genius for commando-style raids. He was also well connected: a grandson of former U.S. president Zachary Taylor, he was the nephew of Confederate president Jefferson Davis.

By the time Tallahassee ducked into Halifax Harbour on August 18 to take on coal, a dozen Union gunboats were in pursuit. Wood had reason to expect a warm welcome. Halifax was notorious as a base for Confederate spies and ships running the blockade on Southern ports. Members of the city’s elite openly supported the Rebel cause.

There was resentment over the North’s belligerence toward Britain and its colonies and sympathy for the underdog South. “They hate the Yank as bad as we do,” observed a Confederate agent, who dubbed Halifax “a hot Southern town.”

The British and Nova Scotia governments were determined to prevent Tallahassee’s visit from escalating into another crisis. Lord Lyons, the British envoy in Washington, cabled Halifax with a warning – couched in diplomatic understatement – that the Lincoln administration was “a good deal disturbed” to learn Tallahassee was in port.

The Royal Navy admiral in charge of the Halifax station and the colony’s lieutenant governor ordered Wood to leave within 24 hours, the tightest deadline the British could impose on a belligerent vessel visiting their ports. A 12-hour extension was later granted but the message was clear – Confederate raiders would not be “coddled” in Halifax.

Wood and his crew had exposed the Union’s vulnerability at sea and spread panic among Northern ship owners, but the real damage was to the Confederate cause. The embarrassed Union Navy was forced to tighten its blockade of Wilmington, North Carolina cutting off one of the South’s last overseas supply routes. And, as Tallahassee’s crew had discovered, Southern raiders could not expect to find refuge in British colonial ports, regardless of how welcoming the populace might be.

(This Information extracted from article by Dean Jobb who is the author of Empire of Deception, the true story of a master swindler in 1920s Chicago who escaped to a new life in Nova Scotia, published in 2015 by HarperCollins Canada)..

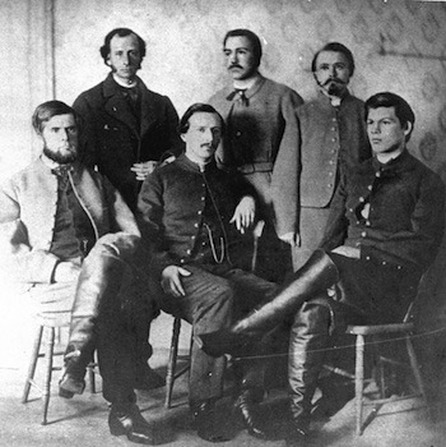

CONFEDERATE RAIDERS AFTER THEIR CAPTURE IN CANADA

CONFEDERATE RAIDERS AFTER THEIR CAPTURE IN CANADA

In the Northernmost Land Action of the Civil War twenty Confederate soldiers attacked the village of St. Albans, Vermont on October 19, 1864. The raid was planned to avenge assaults on Southern cities, to obtain money needed by the Confederacy, and to cause confusion and panic on the Northern border. The raiders robbed three banks of more than $200,000, killed one citizen and wounded two others, stole a number of horses, and tried unsuccessfully to burn down the town. The Confederates, with Vermonters in close pursuit, escaped across the Canadian border. Eventually several were captured and arrested by Canadians. The attack initially caused panic at the local, state, and federal levels. Plans were quickly devised to send a special troop train to St. Albans. But, when it was learned that this raid was a minor, isolated incident, a smaller military contingent was dispatched to guard the city and calm its citizens. Rumors of more attacks along the border stirred up fears until winter. Americans were outraged when the Southerners were initially freed on a legal technicality and sent the stolen money south before they were rearrested. Canada further angered the United States when its courts refused to extradite the raiders and eventually released them. This incident weakened the already strained relationship between America and Great Britain, resulting from the latter’s continuing sympathies for the Confederacy.The story of the St. Albans Raid has all the makings of a silver-screen drama. In fact, a 1954 movie, "The Raid" did just that, although it played fast and loose with the facts.The youthful, dashing and real-life lead character, Confederate Lt. Bennett Young, was the small band’s leader. Young took charge of the mission almost right from the start, recruiting other Confederates who, like himself, had escaped from Union prisons and found their way into Canada.

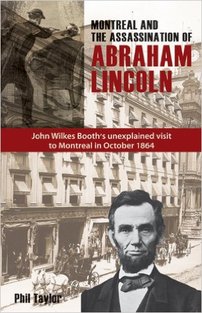

When John Wilkes Booth was shot twelve days after killing Abraham Lincoln in April 1865, a money order for $184,000 drawn from a Montreal Branch of the Ontario Bank was found in his coat pocket. Six months before the assassination in October 1864, Wilkes Booth made a heretofore-unexplained visit to Montreal. He checked into a room in Montreal's plush St. Lawrence Hall Hotel, 13 Great Saint James Street on October 18,1864. The Confederate Secret Service operation in the officially neutral British Province of Canada had set up its headquarters in the St. Lawrence Hall Hotel. The day after Wilkes arrived, Confederate soldiers launched the infamous raid on St, Albans, Vermont. The raiders, like the Wilkes booth conspirators, were financed by the Ontario Bank of Montreal.

Phil Taylor's book "Montreal and the Assassination of Abraham Lincoln" is a fascinating investigation that sheds new light on a little known but crucial aspect of a critical event in 19th century history.

Phil Taylor's book "Montreal and the Assassination of Abraham Lincoln" is a fascinating investigation that sheds new light on a little known but crucial aspect of a critical event in 19th century history.

CANADIAN HOME GUARD DEFENDING AGAINST THE FENIANS

CANADIAN HOME GUARD DEFENDING AGAINST THE FENIANS

Even after the cessation of hostilities in 1865, the U.S. threat to Canada continued, with Irish-American Fenians storming into Canada in the ludicrous dream of capturing it and holding it ransom so that Britain would be forced to set Ireland free. The raids were enough to topple an anti-Confederation government in New Brunswick and eventually led to that colony entering into Confederation with Nova Scotia, Canada East and Canada West, on July 1, 1867.

The Civil War and subsequent actions also had an important effect on discussions concerning the nature of the emerging federation. Many Fathers of Confederation concluded that the secessionist war was caused by too much power being given to the states, and thus resolved to create a more centralized federation. It was also believed that too much democracy was a contributing factor and the Canadian system was thus equipped with checks and balances such as the appointed Senate and powers of the British appointed Governor-General. In reaction, a guiding principle of the legislation which created Canada – the British North America Act was peace, order, and good government. This was a collectivist antithesis to American individualism that became central to Canadian identity.

The Civil War and subsequent actions also had an important effect on discussions concerning the nature of the emerging federation. Many Fathers of Confederation concluded that the secessionist war was caused by too much power being given to the states, and thus resolved to create a more centralized federation. It was also believed that too much democracy was a contributing factor and the Canadian system was thus equipped with checks and balances such as the appointed Senate and powers of the British appointed Governor-General. In reaction, a guiding principle of the legislation which created Canada – the British North America Act was peace, order, and good government. This was a collectivist antithesis to American individualism that became central to Canadian identity.

HARRIET TUBMAN MADE 13 TRIPS ON THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD TO GUIDE OVER 70 PEOPLE TO FREEDOM

HARRIET TUBMAN MADE 13 TRIPS ON THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD TO GUIDE OVER 70 PEOPLE TO FREEDOM

In 1853 John Henry Hill, a young Virginia slave just about to be handcuffed and led to the auction block pulled a hidden knife sending his tormentors scrambling for safety He disappeared into the surrounding city and soon found himself in the care of the Underground Railroad, the secret network of safe houses ferrying escaped slaves to freedom in Canada. After a nine month odyssey, he disembarked at Toronto and took his first steps into the “Promised Land” of British North America. "I have seen more Pleasure since I came here than I saw in the U.S. the 24 years I served my master,” he wrote to William Still, the Underground Railroad’s main agent in Philadelphia. On balance, Canada's record in slavery matters, though not perfect, was very creditable. The actual number of slaves had been dwindling steadily when slavery was finally abolished throughout the British Empire in 1834. In the meantime Quebec Governor Guy Carleton had refused to give back 3.000 slaves to George Washington at the end of the Revolutionary War. and the Underground Railroad admitted approximately 40,000 fugitive American slaves to their freedom in Canada enraging Southerners and inspiring abolitionists. Many U.S. anti-slavery leaders lived at times in Canada, including John Brown, Josiah Henson (Harriet Beecher Stowe's original Uncle Tom) and Harriet Tubman (who regarded herself as Canadian).

A mere 14 years after John Henry Hill's escape, the lands of Canada would seem just as welcoming to a man who had given up his political career, his fortune and even his freedom to ensure that men like Hill remained enslaved. In May,1867, few Canadians noticed when a train trundled into Montreal carrying Jefferson Davis, the deposed president of the Confederate States of America. Davis was a marked man blamed by Northerners and Southerners alike for the deadliest war in U.S. history, and after a harrowing train journey through New York, Davis was just happy to be in a country where few recognized him.There had been a time not too long before where Davis could have assumed that history would remember him as a second George Washington, leading a righteous revolution against an overbearing oppressor. Instead, his Confederacy was under military occupation, 500,000 of his countrymen were dead, and slavery had been permanently abolished. (from a Justin Harper article, July 25, 2014)

A mere 14 years after John Henry Hill's escape, the lands of Canada would seem just as welcoming to a man who had given up his political career, his fortune and even his freedom to ensure that men like Hill remained enslaved. In May,1867, few Canadians noticed when a train trundled into Montreal carrying Jefferson Davis, the deposed president of the Confederate States of America. Davis was a marked man blamed by Northerners and Southerners alike for the deadliest war in U.S. history, and after a harrowing train journey through New York, Davis was just happy to be in a country where few recognized him.There had been a time not too long before where Davis could have assumed that history would remember him as a second George Washington, leading a righteous revolution against an overbearing oppressor. Instead, his Confederacy was under military occupation, 500,000 of his countrymen were dead, and slavery had been permanently abolished. (from a Justin Harper article, July 25, 2014)

JEFFERSON DAVIS IN 1885

JEFFERSON DAVIS IN 1885

Jefferson Davis, gaunt and weakened by two years in a military jail, had headed north to join his exiled family in a crowded Montreal boarding house and begin looking for a job. Mostly, though, the 60-year-old was depressed. Davis had planned to use his time in Canada to pen a memoir about the short-lived Confederate Government. But, overcome by solemnity, he shelved the project, telling his wife “I cannot speak of my dead so soon.” Six years before, Davis’ doomed Confederacy had begun in a burst of parades, bunting, “Secession Balls,” and celebratory cannon fire. The ex-Southern leader was now arriving in Canada just as Canadians were preparing to undertake their own celebrations.

In just a few weeks, on July 1, 1867 fireworks and brass bands would usher in the first Canada Day, although Canadians would call the holiday Dominion Day until 1982. It was no coincidence that Canadian Confederation came together just as the United States was clearing away the ashes of the Civil War.The 2.6 million inhabitants of British North America had been rightly spooked at the sudden appearance of 2.2 million Americans in arms, and the United States was not coy about the prospect of a third U.S. invasion of Canada. Northern troops even had a cheery marching song boasting that when they were done with the South, they would swing north to sever Canada “from Britain’s crown.” Thus, while mid-19th-century Canadians likely disagreed with Davis’ stance on human bondage, they welcomed him as a leader who had experienced exactly what they had long feared: A ruthless, all-out invasion by the armies of the United States. So, for the few months until the chilly Canadian weather sent Davis back home to the land of cotton, he found himself feted as a celebrity. A Montreal printer, John Lovell, allowed Davis and his family to live in his mansion.

At the Theatre Royal, he was welcomed with a standing ovation and peals of Dixie, the South’s unofficial anthem. And, in July, when Davis journeyed to Lennoxville, Que., to visit his son at college, his train was greeted by cheering Canadians.“I thank you most kindly for this hearty British reception, which I take as a manifestation of your sympathy and goodwill for one in misfortune,” he told the crowd in an impromptu speech. Canada was only six days old then, and it would soon go on to achieve everything Southerners had hoped for the Confederacy: A nation stretching from sea to sea, a transcontinental railroad and the reassurance of 150 years of secure borders. Davis told the crowd of new Canadians he hoped they would “ever remain as free a people as you are now.I hope that you will hold fast to their British principles, and that you may ever strive to cultivate close and affectionate connection with the mother country. Gentlemen, again, I thank you.” ( Information gathered from an article by Tristen Hopper in the National Post, July 26, 2014).

JACOB THOMPSON

JACOB THOMPSON

In better times Davis had created a spy network stationed in Toronto. Spy leader Jacob Thompson who had resigned as U.S, Secretary of the Interior at the outbreak of the war, organized Confederates and their Canadian sympathizers to run communications for, and weapons to the South. In Halifax, money was made by selling supplies and information to Southern blockade runners and the Northern ships pursuing them. Thompson distributed and distracted Northern military operations with raids to free Confederate prisoners. He had yellow-fever-infected clothing distributed in Northern cities and plotted to burn Manhattan.

Many other Confederate leaders fled to Canada, including General George Picket, who led the Confederate Charge at Gettysburg known as the 'High Water Mark' for the Confederacy.

SIR JOHN A MACDONALD

SIR JOHN A MACDONALD

The Civil War period was one of booming economic growth for the BNA colonies. The war in the United States created a huge market for Canada's agricultural and manufactured goods, most of which went to the Union. Maritime ship builders and owners prospered in the wartime trade boom.

After the war many Americans thought that invading or annexing lands to the north would give the victorious Union army something to do. In 1860 William Henry Seward , the United States Secretary of State praised the people of Rupert's Land (The area once known as Rupert's Land is now mainly a part of Canada, but a small portion is now in the United States) for conquering the wilderness and creating a great state for the American Union. In the election of 1864 the Republican Party used annexation of BNA as a means to gain support from Irish Americans and the land-hungry. An annexation bill was passed in the United States House of Representatives in July of 1866. It intended that the United States acquire all of what is now Canada. Because Britain had been so supportive of the Confederacy the U.S. demanded a massive sum in reparation. American and British officials discussed ceding Canada to the United States as a way to settle the claims. Prime Minister John A. Macdonald was involved in the conversations.

Whether based in reality or not, the fear of annexation played a definite role in the achievement of Canadian Confederation and in shaping its constitution. Seeing the horror of war that resulted from the divisiveness of American federalism, the Fathers of Confederation decided that Canada should have a stronger federal government than the one south of the border.

John A. Macdonald emerged as the nation-building hero that he was, fending off American threats of annexation and holding off British politicians who sought to cut Canada loose. Not only did the Civil War pose a direct military threat to Canada, it derailed the economic strategy of the British North American provinces. Canadian political leaders needed a wholly new approach to cope with the crisis that confronted them and they rose to the challenge. It was Macdonald who presided over the completion of Confederation, the creation of a transcontinental Dominion, and the building of the railway that stitched it together. It was decades before Canada would gain control of its foreign and defense policies. Eventually Canada beat the odds facing all challenges and its enduring problems between English and French to become recognized universally as one of the most successful human habitats on the planet.

But perhaps the most lasting impact that the Civil War had on Canada was Sir John A. Macdonald's conviction that strong states' rights were "that great source of weakness," which led to the war. That's why Canada emerged in 1867 with a strong federal government - including an unelected Senate, - which to this day fosters endless debate between the believers of federal rights and provincial rights.

After the war many Americans thought that invading or annexing lands to the north would give the victorious Union army something to do. In 1860 William Henry Seward , the United States Secretary of State praised the people of Rupert's Land (The area once known as Rupert's Land is now mainly a part of Canada, but a small portion is now in the United States) for conquering the wilderness and creating a great state for the American Union. In the election of 1864 the Republican Party used annexation of BNA as a means to gain support from Irish Americans and the land-hungry. An annexation bill was passed in the United States House of Representatives in July of 1866. It intended that the United States acquire all of what is now Canada. Because Britain had been so supportive of the Confederacy the U.S. demanded a massive sum in reparation. American and British officials discussed ceding Canada to the United States as a way to settle the claims. Prime Minister John A. Macdonald was involved in the conversations.

Whether based in reality or not, the fear of annexation played a definite role in the achievement of Canadian Confederation and in shaping its constitution. Seeing the horror of war that resulted from the divisiveness of American federalism, the Fathers of Confederation decided that Canada should have a stronger federal government than the one south of the border.

John A. Macdonald emerged as the nation-building hero that he was, fending off American threats of annexation and holding off British politicians who sought to cut Canada loose. Not only did the Civil War pose a direct military threat to Canada, it derailed the economic strategy of the British North American provinces. Canadian political leaders needed a wholly new approach to cope with the crisis that confronted them and they rose to the challenge. It was Macdonald who presided over the completion of Confederation, the creation of a transcontinental Dominion, and the building of the railway that stitched it together. It was decades before Canada would gain control of its foreign and defense policies. Eventually Canada beat the odds facing all challenges and its enduring problems between English and French to become recognized universally as one of the most successful human habitats on the planet.

But perhaps the most lasting impact that the Civil War had on Canada was Sir John A. Macdonald's conviction that strong states' rights were "that great source of weakness," which led to the war. That's why Canada emerged in 1867 with a strong federal government - including an unelected Senate, - which to this day fosters endless debate between the believers of federal rights and provincial rights.

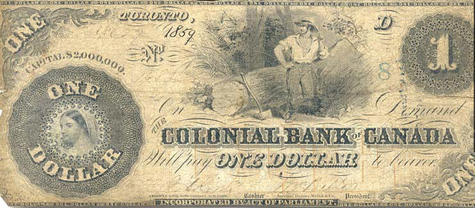

There has been some great opportunities for some Canadian "CROSS BORDER SHOPPING" over the decades but nothing has come close to the opportunities during the Civil War. On July 11, 1864 the Canadian dollar reached an unbelievable all-time high of $2.78 (U.S.). Confidence in the U.S. dollar was shaky and was further weakened by a Southern raid on Washington and Baltimore. It bottomed out at 36¢ (Canadian).

If the dollars were to be as far apart today as they were in 1864, a Canuc could be enjoying the Mother of all cross-border shopping days. A 2014 Honda Accord coupe advertised in Buffalo for $24,415 would cost you $8,789 (Canadian). A 12-pack of Budweiser beer at $9.99 (U.S.) would be yours for $3.60.

There has been some great opportunities for some Canadian "CROSS BORDER SHOPPING" over the decades but nothing has come close to the opportunities during the Civil War. On July 11, 1864 the Canadian dollar reached an unbelievable all-time high of $2.78 (U.S.). Confidence in the U.S. dollar was shaky and was further weakened by a Southern raid on Washington and Baltimore. It bottomed out at 36¢ (Canadian).

If the dollars were to be as far apart today as they were in 1864, a Canuc could be enjoying the Mother of all cross-border shopping days. A 2014 Honda Accord coupe advertised in Buffalo for $24,415 would cost you $8,789 (Canadian). A 12-pack of Budweiser beer at $9.99 (U.S.) would be yours for $3.60.

In fact, there was cross-border shopping in 1864. Back then, Buffalo offered the added attraction of being by far the biggest city in the region. Its population was 90,000, about double Toronto’s. On Main street you could stay at the American Hotel, where newly elected President Abraham Lincoln gave a speech in 1861, or shop at S. Bergman, ready made clothing, which “always had on hand a large assortment of Cloths, Cashmeres, Vestings and Trimmings.”

Some merchants courted Canadians with ads in papers on this side of the border. In the St. Catharines Constitutional, Wilson C. Fox, “Dealer in Fruits, Oysters, Liquors and Cigars,” listed two Buffalo locations, one of which was next to the Metropolitan Theatre. It also touted a “Billiard Saloon, with seven of Sharpe’s best Tables.” Blodgett & Bradford advertised pianos “warranted to give satisfaction” for $150 to $350. The company specified payment in “Gold or Canada Currency.” (Information gathered from an article by Cec Jennings in The National Post, July 11, 2014).

Some merchants courted Canadians with ads in papers on this side of the border. In the St. Catharines Constitutional, Wilson C. Fox, “Dealer in Fruits, Oysters, Liquors and Cigars,” listed two Buffalo locations, one of which was next to the Metropolitan Theatre. It also touted a “Billiard Saloon, with seven of Sharpe’s best Tables.” Blodgett & Bradford advertised pianos “warranted to give satisfaction” for $150 to $350. The company specified payment in “Gold or Canada Currency.” (Information gathered from an article by Cec Jennings in The National Post, July 11, 2014).

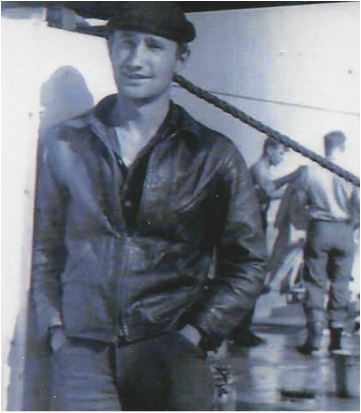

Of course the relationship between Canada and the U.S. has evolved over the years. Young Canadian and American men fought arm in arm in two World Wars, Korea and many peace keeping missions. World War 2 brought Canada and the U.S together like never before. My father spent most of the war escorting merchant ships across the Atlantic. The Battle of the North Atlantic was the longest battle of the Second World War and possibly the most decisive of the conflict. It was also a battle in which Canada was not only one of the main combatants but it stretched deep into Canadian territory and impacted the homeland directly. Winston Churchill stated that "The Battle of the Atlantic was "the only thing that ever frightened me." I'm sure you heard of the German "wolf packs" and their paths of destruction across the Atlantic. The My wife's father spent the entire war on the front lines, He saw action in Africa then moved onto Italy-including the Adriatic Coast and through the infamous Gothic Line and then onto Rimini. He left Italy for France then moved on to Belgium and then into Germany. He was finally escorting prisoners to Den Helder, Holland from Rotterdam. At war's end he returned to Canada aboard the Queen Elizabeth. Some of the personal stories are horrific and bonds were created within the allied soldiers that can never be appreciated by those that were not there. No PTSD allowed for these guys. When the War was over they got their medals, a homecoming parade and then were expected to integrate back into society.......and most did just that......working hard, raising families and locking away the worst of what they saw.

SANDY'S DAD-GUNNER, 15th FIELD REG.,110th FIELD BATTERY MY DAD- STOKER, FIRST CLASS. ROYAL CANADIAN NAVY

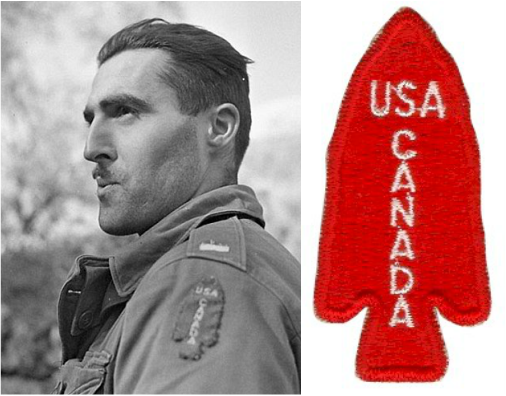

LIEUTENANT j. KOSTELIC PROUDLY WEARING THE UNIFORM OF THE "U.S -CANADIAN JOINT FORCE

LIEUTENANT j. KOSTELIC PROUDLY WEARING THE UNIFORM OF THE "U.S -CANADIAN JOINT FORCE

The Mutual Respect Continues

On February 3, 2015 surviving members of the joint American-Canadian strike force gathered with families of the unit’s deceased veterans for a ceremony in their honor inside the U.S.Capitol. They traveled to receive

America’s highest civilian honor, the Congressional Gold Medal. This honor was bestowed upon the 1st Special Service Force. The joint American-Canadian strike force, nicknamed the “Devil’s Brigade,” was among the deadliest commando units of World War II and the model for modern-day special forces such as the Navy seals. They jumped out of airplanes and parachuted behind enemy lines. Under the cover of night, they scaled mountains and engaged in hand-to-hand combat. They could storm a beach in an amphibious landing or ski across rugged terrain with guns strapped to their backs. They could have been big-screen action heroes—and they did, in fact, inspire a Hollywood movie—but their exploits were all too real. After a successful raid the unit always left a calling card saying "the worst is yet to come."

Now, more than 70 years after they left the battlefields of World War II, the men of the 1st Special Service Force have received America’s highest civilian honor—the Congressional Gold Medal.